December 14, 2023

Webinar: How to De-escalate Conflict

Written by Rachel Eddins

Posted in Relationships, Couples, Marriage, Webinars and with tags: Communication, Relationships, couples

This Focus on Wellness (FOW) event will help couples experiencing conflict slow down the conversation and connect with their internal thoughts and feelings to establish a better foundation that is focused on emotional understanding and regulation – that bonds the couples rather than divides.

Attendees will learn how to:

- Learn how to recognize, talk about, and cope with negative emotions

- Learn what escalation looks and feels like

- Build a deeper understanding of the patterns and cycles that overwhelm couples

- Provide tools and foundational skills that can be applied to communication

- Establish a deeper individual understanding of emotions and the nervous system

This webinar is facilitated by Diana Parlante, LMFT- A. Diana is under the supervision of Dr. Jennifer Kendall, PhD, LMFT-S

Watch a replay of the presentation here.

How to De-escalate Conflict

This is a webinar on the topic of de-escalation for couples. It is presented by Diana Parlante, a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist Associate. This is a focus on wellness webinar.

This is a free monthly webinar where therapists from Eddins Counseling Group present on varying topics that they’re passionate about, they care about, and they’re informed about. It is a free service for the community just to make sure that if there’s any additional support that maybe therapy doesn’t feel like a good fit or just good-to-know information that we have access to.

Diana Parlante is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist Associate with a bachelor’s in Human Development and Family Studies, and a master’s in Marriage and Family Therapy.

She exclusively wanted to work with couples since she was in grad school. According to Diana, a lot of good can come from a healthy, very enjoyable, well-bonded relationship.

With symptoms of anxiety and depression, there’s a lot of overlap if there is some distress or unmet need in an intimate relationship.

What Does Escalation Look Like?

- Raised voices

- Saying things we may regret or don’t mean

- Silence or walking away

- Protective parts

- What we have learned to do when in distress

- When dishes are no longer the dishes

- When a connection is lost

When we’re talking about escalation, it’s really helpful to talk about what escalation looks like in an intimate relationship. This can vary within different relationships, especially for different people.

But it can be measured by raised voices, saying things we may regret or don’t mean, some silence or walking away (turning them back, where we’re not actually communicating with one another, where we’re essentially just separating, not feeling that bond, not feeling heard, not feeling understood). These pieces can be seen as protective parts.

When the voice is being raised we’re yelling, or if we’re shutting down or going small, going internally within our body. We’re feeling unsafe and we’re utilizing the protective parts that we’ve learned throughout our life or whenever we are feeling that sense of distress.

There is an example of “when the dishes are no longer about the dishes”. So we’re arguing or maybe we’re talking about things like the dishes, but it’s with so much emotion, so much power that we’re really not talking about.

There’s a lot of vulnerable pieces underneath it, and then this larger sense of connection is lost. That’s how we can measure escalation, especially when we get into that space of either going internally or going externally.

The internal being the silence and the external being raised voices. And people tend to lean into one style or the other.

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalyptic is a Gottman theory. Gottman is one of the big theorists in the therapy world who specifically has models for couples and couples therapy.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalyptic are:

- Criticism,

- Contempt,

- Defensiveness, and

- Stonewalling.

Criticism

- Criticism vs feedback

- Assumption

- Always and never

- Creates a sense of rejection and hurt for the receiver

- Likely to fall into a larger more frequent pattern

- Protective part

- “I don’t feel like a priority”

Criticism tends to look very specific and it is very different from feedback.

Feedback is: “I really wish that you did something specific. I wish you had taken the garbage out.”, or, “Hey, I noticed that this morning you didn’t leave and say goodbye.” Just feedback with the nature of wanting to connect.

Criticism is a larger assumption about a partner. A partner being maybe a little hurtful, maybe a little selfish, a little harmful. This tends to look like “always or never”. It creates a sense of rejection and hurt for the person receiving the criticism.

This can turn into a larger pattern – a pattern of reaching out and seeking connection or being seen by a partner that is being conveyed as harsh.

Again, this is a protective part in the larger attachment piece: “I don’t feel like a priority; I don’t feel important to you; I don’t feel like I matter; I don’t feel like you see me.”

Instead of leaning into the vulnerability because we are in protection, we are in distress, we’re unable to access that part of vulnerability. It comes through as criticism.

Example of Criticism:

Complaint: I was scared when you were running late and didn’t call me. I thought we had agreed that we would do that for each other.

Criticism: You never think about how your behavior is affecting other people. I don’t believe you are that forgetful. You’re just selfish. You never think of others and you never think of me. So then you never think of me.

Therapy is what I would typically latch on to. I would lean right into that because it’s a little softer. And it conveys a little bit or it deepens into that attachment piece.

But you can also see the behaviors and the assumptions. The assumption that you are selfish on top of the behavior that is maybe causing that sense of unsafe come up in the person who’s criticizing.

Defensiveness

- Response to criticism

- Reverse blame

- Can escalate the conflict further

- Protective part

- Justification to end the conversation

- “I’m not good enough”

Defensiveness is typically a response to criticism. It’s a way of reversing blame, where if you’re becoming a little bit more defensive or leaning into a defensive part, not acknowledging the hurt or the behavior that then caused the criticism in the partner.

It can escalate the conflict further, especially if it’s reverse blame for someone who’s leaning into criticism or wants a sense of connection.

Again, this is another protective part. I see this as justification to end the conversation, I see that you’re upset. I don’t know what to do with it.

And I don’t know how to communicate to you that I care in this larger assumption or attachment wound of “I’m not good enough”. Nothing you’re going to say is going to fix this.

Example of Defensiveness:

Question: “Did you call Ross and Rachel to let them know that we’re not coming tonight, or did you forget like you always do?”

Defensive response: “I was too damn busy today. You know what, Monica? You should know how busy my schedule is on Wednesdays. Why didn’t you just do it?”

Non-defensive response: “Oh no. I forgot. I should have asked you to call. I knew my day would be packed. That’s my fault. Let them call them right now.”

That reverse coming forward as defensive or protective. The goal is to get non-defensive responses and acknowledge the hurt or the question by the person or the other partner.

Contempt

- Larger assumption of partner

- Mocking

- Name-calling

- The greatest predictor of divorce

- You vs. you do

- “I don’t matter and I never have”

Contempt is an even larger assumption of a partner. We see behaviors like mocking and name-calling, and just a general increase of harshness compared to criticism.

For Gottman, contempt is one of the greatest indicators or predictors of divorce.

The distinction between criticism and contempt is “you are versus you do”, the behavior versus who you are and who you’re defined as a partner, a husband, a wife, or a significant other.

The deeper part is “I don’t matter and I never have”. This is a very, very desperate attempt for connection, where it looks like from the receiver of this.

What the person who is experiencing that contempt is looking for is to be seen and to feel like they matter. But again, protective parts don’t create a connection, they create a disconnect.

Example of Contempt:

“You’re tired, cry me a river. Who watches the kids? I’m running around like mad to keep this house going. And all you do when you get home from work is flop down on that sofa like a child and play those idiotic video games. I don’t have time to deal with another kid. Could you be any more pathetic? You’re a lousy husband. I can’t even look at you right now. You disgust me.”

This isn’t an abnormal pattern that couples fall into. These are protective parts. These are moments that maybe don’t define a particular relationship, but we want to manage.

Stonewalling

- Shut down

- Silence

- Turned back

- Response to contempt

- Difficult to stop

- Protective part

- Flooded

- Numb

- “Nothing I say will fix this. I’m worthless.”

Stonewalling is not particularly verbal. It’s a visible shutdown. It’s visible silence when you turn back. It can feel like your partner’s turned away from you, and they might also be physically turning away from you.

Again, this is a response to contempt. This is the more extreme part of defensiveness when the intensity is cranked up a little bit.

This pattern of stonewalling is really difficult to stop because it’s a really large protective part. It’s typically associated with flooding or feeling numb or disassociated from the body.

It’s believing the contempt. And it’s leaning into that while also compromising identity.

The stonewall is very internal, it’s very quiet, and you can see it in body language. Eyes can glaze over, like what we look at for disassociation when there’s any instance of trauma. Again, these are all protective parts.

Example of Stonewalling:

Stonewalling isn’t particularly verbal. This is what we would use in situations where stonewalling is about to occur. So this is the response.

“Alright, I’m feeling too angry to keep talking about this. Can we please take a break and come back to it in a bit? It will be easier to work through this after I’ve calmed down.”

This is going to be a big part of what we talk about today, how to manage the escalation, how to build inside of self so “the dishes aren’t just the dishes”, and how to implement that in your relationship.

That’s our larger goal today: build inside of yourself and what you can actually do in your relationship to slow this process down and not allow these four protective parts to control or dictate your relationship.

Effective Emotional Regulation

This is a little quote from Sue Johnson, who’s the creator of the model that I use. Emotionally focused therapy is one of the most effective models for couples therapy specifically.

It’s really helpful in bringing a lot of understanding to couples about not only what’s going on in your body, but how your response, how your experience of emotion and your life prior to this relationship, and your protective parts influence your intimate relationship today, how it informs and influences your conflict as well.

Effective emotional regulation is a process of moving with and through emotion rather than reactively intensifying or suppressing it and then being able to use this emotion to give direction to oneself. – Sue Johnson

We’re using that insight. We’re using that emotion not to create a response in our partner, but to create more insight of self. We use that insight to inform and bid out to partners.

We want closeness, reactivity, and emotions of not feeling seen, not feeling enough, and feeling harmed and hurt. And we don’t want that to create reactivity to push partners away. We want it to bring it in closer.

Attachment Theory

The Lens

- Wired to connect

- Wounds and injuries arise in childhood

- Deeper unmet attachment needs influence conflict and connection

- Couples are resilient and desire growth

- Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT)

This lens can really helpful in creating long-term change as opposed to specific exercises or scripts that I’ve seen in couples therapy and even tried. This is a larger assumption where we’re wired to connect.

We are bonding mammals. We are made to be around others. It’s what creates comfort.

We have parts of self-regulation and we have parts of co-regulation. But the co-regulation is what we’re looking at because this is a couple series. These injuries or these wounds arise from childhood.

Attachment is not just about childhood attachment, but the bond between parent and child is mimicked and follows us throughout our lives. And they can play out in our intimate relationships where wounds that have occurred in childhood (such as: “I don’t feel like I matter. I don’t feel like I’m important. I’ve learned that I’m a burden.”) play out.

And we seek that comfort. We seek that co-regulation in our intimate relationships.

We look to partners to say: “You are not a burden. You certainly are enough. I love you. I care about you. You’re hurting. I want to be right there with you.” That’s going into the other point here.

The deeper, unmet attachment needs influence conflict and connection.

So the “not good enough”, the feeling like a burden, those come into our conflicts about the dishes. If we want to be seen or understood and just want our partner to come in, do the dishes, and not ask why, and then look at us and say:

“You matter so much. I know you had a really bad day today, and I did the dishes for you.”

We’re not talking about the dishes. We’re talking about the deeper sense of connection and bond, not only with self, but with partner, and how the partner responds to that emotion as well.

Another assumption is that couples are resilient and desire growth. We’re not stagnant people. What works today might not work tomorrow because life can be unpredictable. Sort of going through life where you lose a job or potentially lose a parent or a child or experience a trauma.

We’re inherently resilient because life changes every day. Relationships change too. A relationship needs change as well.

That’s more about the lens, the larger assumption that I’m functioning from today and where I’m coming from, and certainly what I use in a couple’s therapy as well.

Attachment Theory and Adult Relationships

How attachment plays out in relationships

- Secure base

- Accessibility, responsiveness, and emotional engagement

- Emotional balance

- Distress system that follows

- Soft spots

We’re looking for a secure base. We’re looking for a partner to be responsive to our emotional needs. Also, we’re looking for accessibility, responsiveness, and emotional engagement.

Essentially, that means if you are having that bad day or if you’re feeling alone, or if you’ve lost somebody that you care about, if a friendship has shifted if you’re experiencing anything that is inherently human, that is a struggle, and you look to partner to help you co-regulate, you want them to be accessible.

You want them to be responsive and engaged with you. That communicates care. That communicates security.

That’s the larger goal: We’re looking for emotional balance not only within ourselves but within our partner.

When we are maybe feeling that sense of intensity, we are feeling a sense of distress, there’s a system that follows. And the goal is to build insight into that.

Know your soft spots, know your triggers. So you can then bid out for a specific connection. And when you bid out creating clarity for your partner, then they can know: “My partner feels this. My partner doesn’t feel enough. They feel like a burden.”

The larger assumption isn’t that partner is selfish, that they don’t listen, that they don’t care. The assumption is my partner struggles with this, and I never, ever want them to feel that they aren’t enough.

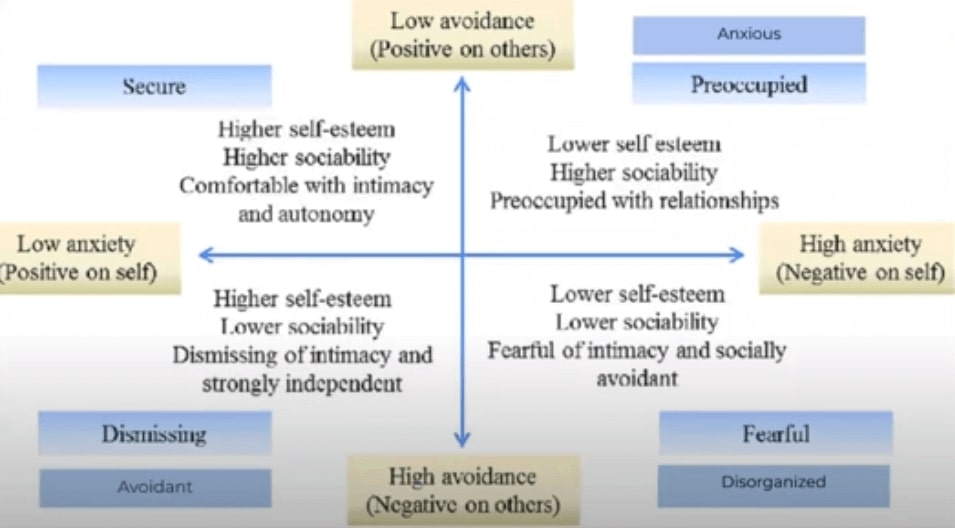

Diagram of Attachment

This is the large diagram of attachment. The attachment theory is something that isn’t super hidden, but sometimes people know a little bit about it if they’ve been to therapy before. In some people, this is maybe a newer understanding of people.

We have the secure attachment, which is the larger goal. I have yet to meet anybody who is securely attached because I think life can just be really challenging and not everybody’s perfect.

An insecure attachment style isn’t a death sentence. It doesn’t make you a burden, and it certainly doesn’t mean that you’re rigid and set in that pattern.

Someone who is securely attached has a positive sense of other and a positive sense of self, which essentially can show up as higher self-esteem, really comfortable in social situations, comfortable with intimacy, and comfortable with autonomy, so independent decision making, (things that they do independently as who they are).

Then when we jump into more of the insecure attachment styles, these can look different. With specific situations, we might lean into a more avoidant attachment style, or we might lean into more of an anxious attachment style.

It changes depending on the severity, but typically, we fall into similar patterns. That disorganized piece at the bottom right is going to be the combination of both.

The avoidant attachment style has a positive sense of self with a negative sense of others. This is what we see with the four horsemen that we talked about earlier, the defensive and the stonewalling pieces.

When things become difficult, the larger tendency is to turn within.

It’s because there’s a negative view of others or a high level of avoidance. People can be scary. People can be harmful. I’ve learned that people are unsafe. I know that I am safe, but I don’t know if other people are safe.

They have a higher sense of self-esteem, maybe lower comfort in social situations, maybe not as comfortable with intimacy, and are very independent. Again, that confident sense of self.

Then we’re going to anxious, which tends to have a positive view of others and a negative sense of self, typically having a lower sense of self-esteem, comfortable in social situations, and tend to be a little focused on relationships because relationships are where people with anxious attachment styles feel the most comfortable and accepted.

When people tend to have a little bit more of an anxious attachment style, the people that they surround themselves with, the safety people negate that anxiousness.

They make that anxiousness feel a little bit more quiet, a little bit less intense. Because it’s external validation because we have a lower sense of internal validation. And then our fearful or disorganized has higher anxiety or a negative sense of self and a negative sense of others.

They have low self-esteem, low social comfort, fear of intimacy, and tend to be a little bit more socially avoidant, tend to be really disorganized, lack of safety with other people.

We can see that with maybe someone who typically might have been anxious or avoidant has a traumatic event where, again, we’re shifting these attachment styles.

They’re relatively consistent, but they’re absolutely able to change and modify, grow, or maybe get a little bit more internally anxious or a little bit more avoidant.

When We Lose the Connection

What we see, feel, and think

- Patterns can become rigid

- Same thought pattern “they always do this” deeper attachment wound “I don’t feel like I matter”

- The Four Horsemen

- Conflict as protest

- “You feel so far away and I can’t do this anymore”

- Faired repair attempts

- Bids for connection that lead to conflict

- Longing for connection – to be seen

- Protective parts – no bad parts

- Change happens when we use more than skills

Patterns can get really rigid, essentially just meaning that when we fall into these protective parts, it’s hard to change. If we feel unsafe, we’re automatically going to go to what makes us feel safe.

If our safe is fighting for the relationship because we need that higher sense of connection, or if it means turning inward and withdrawing.

For someone who is a little bit more of a pursuer, that pursual activates the avoidant attachment style where they then withdraw. And that withdrawal then activates the pursuer.

“You’re turning away, I’m looking for closeness. When you turn away, I want more closeness.” As the person who is turning away, who wants a little bit more independence, a little bit more quiet, a little bit of time to regulate, that pursuer continues to withdraw. So it influences.

I see conflict as a protest. Conflict isn’t inherently a bad thing. It can feel bad when it’s out of control. It can certainly be bad if it’s absolutely out of control. But conflict is typically a protest. Whatever we’re doing now isn’t working.

“You feel so far away and I can’t do this anymore. I can’t do this with you being this far away. I can’t do this with the way that we’re doing it.”

Our failed repairs are attempts, when something happens, if a conflict does arise and we’re either not repairing or we’re trying to repair and it’s just not working. The bits for connection then lead to conflict.

“I’m trying to connect with you. I’m trying to make this better. I want to take ownership. I want to feel close to you. And then all of a sudden it shifts to conflict.”

This larger sense of longing for connection: we want to be seen. We also want to manage our protective parts, knowing when they’re coming out because we do not have that sense of connection or closeness, the protective parts then come out to advocate.

Change happens when we use more than skill. When we use that insight, we use that emotional awareness and that vulnerability to communicate with partners.

That shared experience then changes the meaning. If we have a larger sense of “we can’t repair” or “our relationship isn’t going well and will never change”.

When you experience something that is different, that’s a long-term change. It’s not a script, it’s not a manual, it’s not just a book. We need to feel that shared experience of trust, of connection, of the bond.

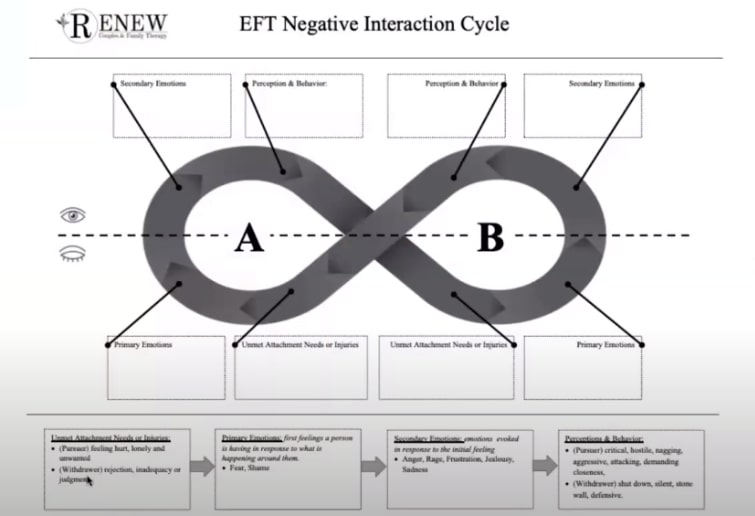

EFT Negative Interaction Cycle

This is a negative interaction cycle. We have partner A and partner B. At the very bottom, we have unmet attachment needs or injuries. We have the Pursuer and we have the Withdrawer.

These are the two little pathways that we take as someone who maybe is more anxious, negative sense of self, positive view of others, and our withdrawer, positive sense of self, negative view of others.

Those unmet attachment needs or those injuries could be for the pursuer, our A partner, not feeling heard, not feeling like they’re wanted, not feeling like they are enough, that sense of hurt. Once that attachment wound is hit, we shift to a primary emotion, which is typically fear, pain, or shame.

And this eye closes, essentially just means that we’re unaware of this. This isn’t something our partner can see, and it’s something that’s just happening internally within us.

Then we transition to what we can see, what we can see, and what our partner can see. Our secondary emotion tends to be anger, rage, rage, frustration, and sadness.

Then we transition to a behavior or perception. For our pursuer, that can look like criticism, contempt, can be demanding, seeking closeness, looking for that bond, but it’s coming off as being critical or harsh.

That harshness then activates our withdrawal, our partner B, who then is going to a sense of inadequacy, a sense of isolation, feeling like a burden, that judgment. And then they transition to a primary emotion of fear, pain, or shame.

Then they go up to something that their partner can see and that they are aware of, which is, again, that anger, that frustration, that sadness. Then transitioning to a behavior or perception of silence, shutdown, stonewalling, and defensiveness.

This is our negative interaction cycle. This is the escalation and it is what we’re trying to get a manage on.

And if we know what the top looks like and we’re really not sure what the bottom looks like, that’s what therapy is really helpful for, to build that insight so it doesn’t feel like you’re doing it alone. But you can absolutely do this at home and by yourself.

If any of this is resonating with you, this can lead to de-escalation. If you know where you’re going, it’ll be easier to communicate that vulnerability with your partner. Hopefully, you get a different response. If we’re changing the system, it’s likely for our partner to change and modify with us. But sometimes the pattern is really rigid and it’s hard to lean into safety. Sometimes it can be easy, sometimes it can be difficult.

By no means do you have to go to therapy to figure this out? I hope that this is helpful for everybody, but sometimes it is helpful to have a third person coming in who is listening to or seeing things that you might not be able to see or access.

The Dance

Pursuer:

- Comfortable initiating difficult discussion

- Larger need for togetherness

- “I need to fix the problem now”

- “I can’t let the problem sit there”

- “In my family, we let it out”

Attempts to get back to safety

- “When I don’t feel you close, I fight for you”

- Engagement

Withdrawer:

- May try to resolve internally or alone

- Need for separateness

- “Nothing I say fixes anything”

- “I get overwhelmed when conflict arises”

- “I need time to process this”

Attempts at safety

- “I need to think about this more because you are important to me”

- Avoidance

This is our dance, just a little bit more clarification here. We have our pursuer, comfortable initiating discussion or difficult discussion, so comfortable with a sense of vulnerability.

The criticism coming through, the one who maybe leans into criticism a little bit more is saying actively protesting, “This is what’s going on. I need something different. You’re over here doing this and it doesn’t feel good.”

They’re comfortable initiating difficult discussions, but not necessarily comfortable with vulnerability.

Again, that pursuer has that larger need for togetherness. This language can be expected quite a lot: “I need to fix this problem. Now, something’s wrong. We need to address it at this very moment. I can’t let this problem sit here (creates some anxiety).” We can’t live with this problem. It just overwhelms the system.

There are also cultural family pieces: “In my family, we let it out.” And that can include yelling and screaming.

Attempts to get back to safety for somebody who is a pursuer are: “When they don’t feel close, I fight for you.” So they engage, they pursue that connection and that engagement from a partner.

We have our Withdrawer who may tend to resolve any discomfort, or upset, internally, and alone by themselves.

They have a larger need for separateness. This larger balance of togetherness and separateness is the human experience. We’re all looking for a little bit more balance.

We don’t want too much togetherness to where we don’t feel valid and have a sense of identity outside of others. We also have this other piece of not wanting too much separateness where we have no sense of connection and feel very isolated and alone.

We’re always seeking balance, but people tend to lean into one of these patterns. Language being: “Nothing I say fixes anything. I get overwhelmed when conflict arises and I need time to process this.”

Maybe for the family or the cultural piece, we don’t acknowledge these things. This is not something we talk about. Attempts to get back to safety.

“I need to think about this more because you’re important to me.” That larger pattern of avoidance.

Window of Tolerance Awareness Worksheet

There is a questionnaire and a handout that I give to my clients to build more insight. We want to know where we go.

We have hyperarousal, which essentially is our pursuer, the abnormal increase of responsiveness or verbal engagement, senses of feeling anxious, angry, or feeling out of control.

Then we have the dysregulation being our raised voices. When things are starting to feel out of control, we’re saying things that we may potentially regret. And the little unicorn float is a window of tolerance.

So if there are external factors, if work is particularly stressful, managing children is a little bit more stressful, maybe on a day-to-day basis, our window of tolerance is thinner. When it comes to our relationship, small things can then create this reactivity or this hyperarousal or hyperarousal.

We want to take care of ourselves, make sure that we’re building insight on where our threshold is and we’re meeting it where it is.

So if we need some quality time, if we need to go on a walk, if we need to talk to a family member, we DO that. We’re slowly expanding the window of tolerance by taking not only care of ourselves but acknowledging where we are.

The hyperarousal is that decrease in responsiveness, going internally, going inward, that feeling of being numb, feeling exhausted, that sense of depression. Again, that sense of disassociation or the body shutting down or freezing.

This is a little checklist that you can go through to see where you land. It doesn’t necessarily mean that always you’ll land in hyperarousal. Sometimes you’ll check things that might be in that category, feeling a sense of tension, rigidness, racing thoughts, but also a sense of memory loss, a sense of shame or embarrassment.

We’re just looking for generally where we go. Obviously, this isn’t rigid where everybody goes to a specific area. Sometimes it’s both. That aligns with our more disorganized attachment style or our fearful attachment style.

How Do We Get to Connection and Safety?

- Emotions aren’t the problem – how we consolidate

- Influence over others

- Be able to self-regulate and change the music

- We can feel emotion but want to express it when managed

- Insight of self – do you know where you are going?

We’ve talked a lot about what escalation looks like, but what do we do now? Connecting on the pieces that we’ve discussed earlier, building more insight into self. Also, not allowing the emotions to feel like they’re the problem.

The emotions themselves are the indicator of what’s going on. You’re feeling something that’s 100% valid. It’s how we consolidate and manage those emotions.

We want partners to be close and to co-regulate typically. But how are we communicating that? The belief that we have influence over others. So if we show up differently, our partner may respond differently.

Being able to self-regulate and change the music. This music and this dance that you and your partner engage in, that you want to be able to change it. You’re inherently resilient. Your relationship isn’t defined by this dance, but it certainly feels like it.

Rather than you being the problem or your partner being the problem, the dance is the problem.

That interaction cycle we just broke down. That is the problem. When the protective parts come out, our partner can’t access us.

And that’s all we’re looking for, is to be accessed, to be co-regulated with, to be comforted. Again, right insight of self, you know where you go.

When we can maintain our emotional balance, the research indicates that we are simply better at sensitively picking up on others’ cues and need for support and then responding in a caring way that they can take in and accept. – Sue Johnson

We’re looking for emotional balance. It’s not to say that we can’t feel anger or we can’t feel sadness.

How we manage those emotions and certainly how we express them if we’re looking for responsiveness. This isn’t something you have to do every day. This is something to de-escalate.

Generally, it’s a good thing to do to know how you feel and what you’re looking for in those moments. We’re not perfect.

We’re going to have moments where we feel anger and it’s going to feel out of control. But we don’t want that to dictate the bond and the connection that you have with your partner.

Things to be Curious About

These are some things to be curious about:

- Does your conflict feel like a consistent pattern?

- Do we have a pursuer? Do we have a withdrawer? Does that resonate with you? And if that pattern is showing up, wanting to dive into that. Has anything I said or anything that we’ve mentioned today resonated with you? Who taught you or who made you feel first? Where did you learn that you’re not important or that you feel unwanted or you feel like a burden? Who has overwhelmed your system first? What’s your first memory of that?

- Where do you go and what influence do you have in your dance?

- Where do you go again? Hyper, hypoarousal? Are you the pursuer? Are you the withdrawer? How do you influence the dance? How do you reach out to your partner?

- Are there consistent soft spots? Are there triggers?

-

- Is there maybe a specific event in your life where someone has taught you (maybe a previous intimate partner) that your needs aren’t important, that you’ve learned to compromise your needs to soothe or maintain a relationship? Sometimes we have really bad relationships that we can heal from, we can talk about, but still, our nervous system remembers, it doesn’t forget.

- Do you notice when the conversation changes or when things shift, especially when they shift sideways?

- Can you notice when you’re vulnerable and accessible, and then all of a sudden you feel your nervous system kick up? You’re feeling your stomach shift. You’re feeling that intensity in your chest. Your heart rate is starting to increase. For example, when I’m nervous, my speech picks up. When I’m escalated, my nervous system assesses a threat. My cheeks get red.

That’s what my body is telling me, and I use that. What my body is sharing with me is important to note. Because if I can’t access the more vulnerable parts of myself, I can guarantee the outcome of that conversation is not going to be a connection. It’s going to be more division.

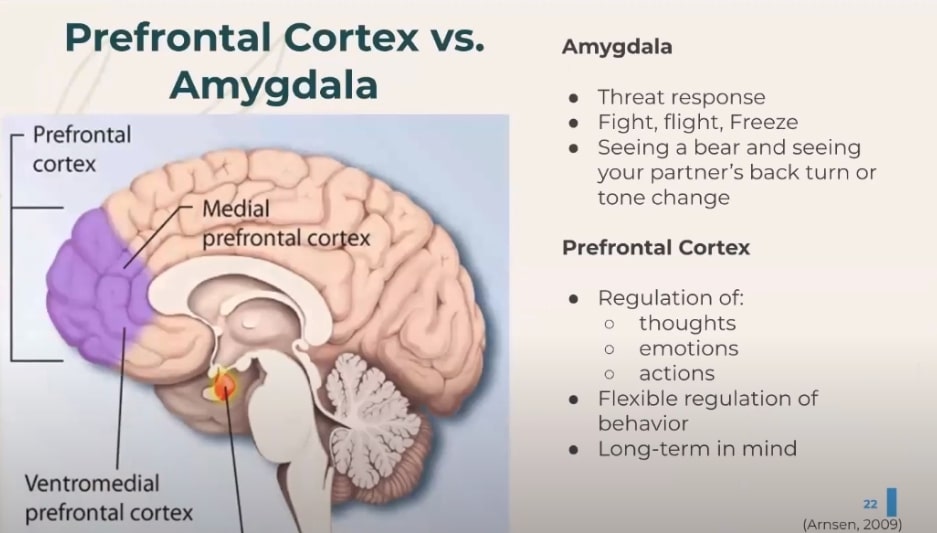

Prefrontal Cortex vs. Amygdala

We have our prefrontal cortex and our amygdala. The amygdala is our “fight, flight, or freeze”. The same response that we see when we see a bear, our body is doing the same thing when we see a tone change in our partner that the meaning is no connection, unseen, validating that attachment.

When we see our partner shift, our brain is going immediately to that part that’s saying: “Oh, my goodness, there’s a threat.” And your body activates in that way. Whether that’s hyper, or hyperarousal, that’s what’s going on in the brain. The amygdala has turned on.

Our prefrontal cortex is the regulation of our thoughts, our emotions, and our actions. This is the more executive part of the brain where there’s a little bit of flexibility. We’re able to get to the regulation of behavior. We’re thinking about and assessing the situation for threats and seeing if that’s the reality we’re living in or if that’s something that maybe our brain and our body are tricking us into.

And we’re in control of these systems. But also we learn that maybe we’re not. Maybe our threat system is a little bit more active, depending on the lives that we’ve lived.

If our threat system or our safety system has been compromised since we’ve been a child, this might not be easy to understand or connect to. It might just feel like a knee-jerk. It’s a protective response.

When the amygdala is on, our prefrontal cortex is not. We can’t access that regulation when our amygdala is on because we’re “fighting a bear”. We’re “fighting for a bear” and we’re fighting for connection. When the amygdala is on, we can’t get to the front and we want to get up here.

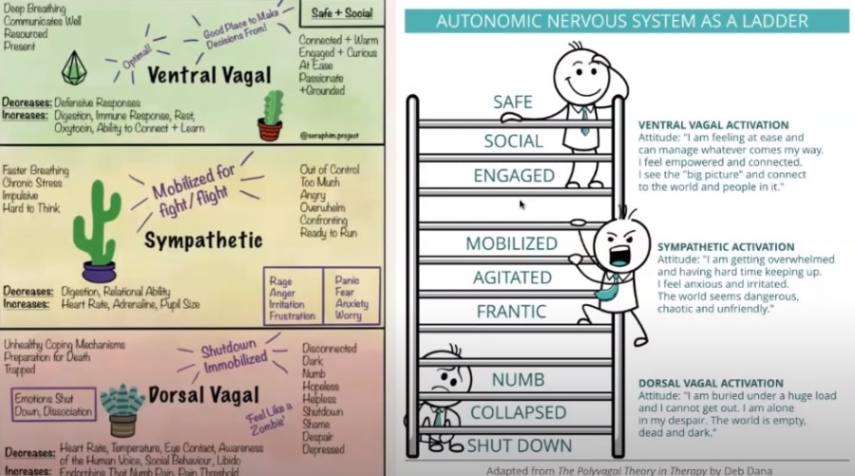

Autonomic Nervous System as a Ladder

This is an indicator of what parts of our brain are on. There’s a lot of language on here that may be a little confusing, but we want to be up on the ladder. We want to be safe, social and engaged. So that’s going to be on our left, our Ventral Vagal, where we’re connected and warm.

This is where we want to be when we’re in vulnerability and when we’re trying to get to de-escalation. f you feel your body changing to out of control, we’re in the yellow now, we’re a little agitated, we’re a little frantic, you need to call a time out. You need to say to your partner:

“You know what? I care so much about you. I came to you today because I wanted a connection because I had a really, really shitty day. And I really want to feel close to you. I want to make sure that you understand me. And I’m feeling my body activate now, and I can’t access the thoughts that I want to share with you. So I need to take a moment. I need to breathe. I need to call a friend.”

You walk away, but you communicate the importance that your partner has for you. “You are important to me, and this is important. I don’t want this to control this pattern to control our relationship.”

Call attention to it. This isn’t working. I’m not in the part of my brain I need to be at. I don’t need to be enraged, I don’t need to be anxious and worried, I don’t need to be in a panic. And you go on a walk, pet your dog, you do whatever you need to do. And then once you’re back in the green, you re-engage with your partner. That is the most important part.

If you call a time-out, revisit.

Go back to your partner and say:

“Where are you? How are you feeling? Are you available?”

If they say yes, you try it again. And even if it doesn’t work the second time, you’re making sure that you’re in the right parts of your brain to really be able to be vulnerable because that’s what you’re looking for. You’re looking for a connection.

We don’t want to be anywhere near the red in these discussions. This is where we get the escalation, the out-of-control, the regret, the hurt, and the even larger disconnection from our partner.

We don’t want to be anywhere near this. The key to de-escalation is knowing where you escalate and where you need to be to be vulnerable.

Turning Inward

When your body says stop

- Heart rate elevated

- Pit in stomach

- Pressure on chest

- Overthinking

- Feeling numb

- Temperature changes

What does your body do? What does your mind do? Does your mind shut off or does it engage further? Increase responsiveness or decrease.

Is There a Consistent Theme?

- Are we hitting the same attachment wound? Are we hitting the same part of you that comes up in all of your relationships?

- Has there been a traumatic event?

- Is there something specific that you learned right from a traumatic event that you haven’t maybe been in the same sense? Is this a soft spot that needs to be incredibly empathetic? Does your partner need to lean into this soft spot to comfort you, to co-regulate with you?

- Has there been consistent hurt in your life?

- Have people told you or made you feel like you’re not important or that you are a burden?

- These are the unmet attachment needs that need to be addressed that then inform the conversations about the dishes or the laundry or the dog or family. “Do you protect me against your family? Am I a part of your family?”

- “Not good enough”

- Unloved

Escalation is Going to Happen

It’s normal

- Managed and within healthy limits

- Creating balance and safety

- Co-regulation and self-regulation

- Often don’t lean into vulnerability

- Requires risks

- Your needs are important

- You are important

- Experiences teach us protective parts

- Unlearning and healing

- Learned that people and unsafe

- You don’t have to do it alone – couples therapy

Life is certainly not pretty. It’s very hard and it’s very challenging. But what do you do to manage and get through it? Create healthy limits.

Know where your limits are, know what your body’s telling you that we’re inherently made to co-regulate and self-regulate. It’s all a balance of self and others.

We often don’t lean into vulnerability as very protective people, we tend to live in a very unsafe world.

Saying “I’m hurt” isn’t as easy as saying “I’m pissed”.

I’m really upset with you and it’s balls to the wall. I’m so mad and everything’s off the table. Maybe that’s not super easy to say, but that’s more comfortable than saying I’m so hurt by our relationship, and I have been for years.

Your needs are so important and you are important. So advocating and regulating for yourself, building that insight into who you are what you’ve learned, and what your life has been, is valuing self.

Experience teaches us these protective parts.

You’re not a burden. You are not to blame.

But the parts that live in you are within your control. As adults, we’re able to manage and control this.

Unlearning and healing is really, really challenging. It’s not easy. If you need support, therapy is always an option.

Leaning into the support of your family and your friends, learning that the people that have made you unsafe and how the body remembers that isn’t always necessarily true. You certainly don’t have to do it alone.

Limits to EFT for Couples

Individual Therapy first

- Active Violence

- Active Affairs

- Addiction

- Trauma

There are limits to emotionally-focused therapy for couples. If there’s any active violence that compromises safety, EFT might not be the immediate solution. We need to do individual therapy first to de-escalate and create some safety in an individual atmosphere. If there’s any active violence, if there’s any active affairs, that at our foundation compromises safety.

Active addiction can do that as well. When we’re married to alcohol, when we’re married to something else besides our partner, things that take priority over our partner, EFT isn’t going to be helpful because there’s a third person in the room.

In cases of severe trauma as well, EFT is not the best. We want to do individual therapy first. That can be emotionally focused individual therapy, but couples is particularly sensitive.

De-escalation is very common. It’s a very rigid pattern, and we need to have some flexibility for that to happen so we can get to de-escalation. If there are these four things happening, it limits our ability to do so, and potentially we can cause more harm, which is the exact opposite of what we want to do.

When Conflict Arises – Now What?

Something that is unique to you and your partner

These are the takeaways, the slower process that you should really lean into. Something that is unique to you and your partner. Your needs, your experiences, and what you’re looking for are all unique to you.

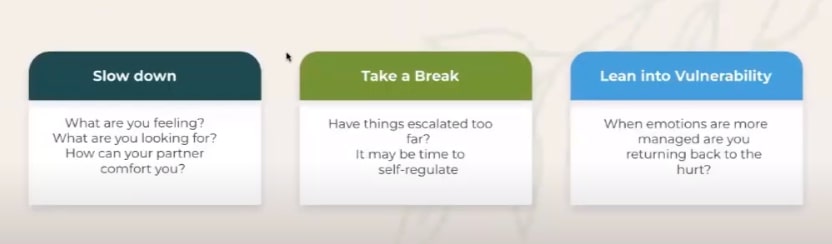

Take this generalized understanding and make it your own. Slow things down. What are you feeling? What are you looking for? How can your partner comfort you? Take a break.

If there’s some escalation, if there’s things that have been said in the past that have gone too far, we certainly don’t want to do that again. We don’t want to limit connection in our bond further.

So take some time. Take a break. Take a time-out. That might feel a little childish, but I think it’s so helpful and it’s a huge key in creating that change.

Self-regulate before we can co-regulate. Then we can lean into that vulnerability once we give our partner access and our partner can then access us. When emotions are more managed, are you returning back to that sense of hurt and sense of longing? You need to lean back into it.

Otherwise, again, you’re feeling alone, and isolated. And this cycle is just going to keep going and going a. And we want to break that. Well, this is the de-escalation we’re talking about.

What if one party wants to self-regulate and connect, but the other isn’t interested and refuses to do so?

It’s really important that I think we have a baseline and a foundation of what a timeout means. I think some people can fall into patterns of “When I see you taking a timeout, that means that I’m not important and that we’re not going to revisit.”

That’s what I understand there, that when the timeout is called, there’s no guarantee that connection is going to be made or timeouts haven’t worked in the past and that needs to be worked through.

That is really the foundation here when it comes to de-escalation, is that timeout is needed because we cannot access co-regulation if we’re in that state of overwhelm.

What is Gaslighting?

Gas lighting isn’t a safe pattern. It can be a protective part. But if it’s labeled as gaslighting with both partners, we want a unit together to fight that sense of gaslighting.

Gas lighting is harmful behavior. We don’t want that in a relationship because that can create a sense of unsafe because we’re living in two different realities. We want to have a shared reality.

Why do people gaslight their partners?

That can be because of varying reasons. My understanding is gaslighting comes from previous trauma. It’s a very big protective part, but also a very harmful part.

I would encourage couples therapy very much or individual therapy if gas lighting is a protective tool. What I hear in that is that there’s been a lot of harm in the past in creating a space where reality is very comfortable for the person who leans into gaslighting.

This is something to be unlearned because again, it doesn’t create that sense of safety within the relationship or within the marriage specifically. The gaslighting behavior is a result of the lack of safety.

That typically again comes from our caregivers, our parents, especially children who have experienced significant trauma in their childhood, will lean into that.

What if you want to establish that middle ground baseline but the partner doesn’t believe in any sort of regulation?

If somebody doesn’t believe in regulation, it means that they can only communicate with you when you’re feeling their emotions. It’s a learned belief and meaning of “I don’t know what I’m feeling unless I’m feeling it. And when I’m advocating at my most passionate, that means that I’m communicating what’s real, what my reality is. I can only communicate with you if I’m in that state of dysregulation.”

What we know, though, is that that’s not necessarily true, and it can create more harm. Because if someone is maybe leaning into high arousal or we’re going within, you can’t access and co-regulate with a partner.

That’s a tricky thing, especially if you have a partner who thinks or believes that the only way they can connect with you is when they’re dysregulated.It’s dysregulation, and we want to get to regulation to where we can co-regulate.

Again, I would encourage individual or couples therapy because it’s hard for partners to really push in this way because it might feel like an attack. It might feel like something meaning to control or to distance further.

It’s hard as a partner to try to navigate beliefs, especially attachment beliefs or family beliefs about dysregulation. It’s a challenging position, but I think if you build that baseline together and you articulate the desire for a time-out, the desire to get to regulation, maybe you’ll see a modification.

But again, it’s hard as a partner to establish that.

What can you try with a person who has narcissistic personality disorder?

It’s going to be hard as a partner to remove or change the system solely. Because your attempts to get to something different might be seen as a rejection by someone who believes that they are “the best”.

It might also not be totally safe for you to push back, depending on how severe the traits are. It might also be the position you’re in as a partner that you can’t really push back.

There are some things that I like to separate on what’s your work as a partner and what’s work for your significant other who might be having specific protective parts that lean into: “I’m the best, I’m right, and you’re wrong.”

There are things that are your work as a partner, and there are things that need to be done on your partner’s side to really lean into that empathy and understanding.

Certain narcissistic personality disorder behaviors are rooted in trauma, especially childhood trauma. So again, as a partner, it’s going to be hard for you to build understanding, to build insight as a partner as opposed to a therapist, or as opposed to somebody who’s not in that direct immediate relationship.

When do things reach a point when it’s not safe to push?

The hard limit is dependent on the person. There’s a reason why couples stay in specific relationships. There was a sense of connection. But when we get so stuck in a pattern, it doesn’t feel like it.

Your limit is your limit. Your hard limit is your own.

Not safe to push is when you feel your body. Your body is going to tell you first. Your nervous system is going to tell you that it’s unsafe. We tend to feel things in our body before our mind can catch up necessarily.

I imagine you have a feel for whenever you’re leaning in or you’re trying to get your partner to see you or to understand you or to just empathize with you, to be there with you, and you’re not getting the response that you’re looking for or if it’s turning to violence. Unsafe is when I lean into violent behaviors, or maybe controlling behaviors.

In extreme situations, when is the hard limit and when would a relationship fail?

Violence is something very tricky to come back from. But that’s not necessarily true.

We can come back from instances of violence.

I would say if there’s an extreme sense of control and leaning into “you’re the problem”, this will never change, or the language of “you are unlovable”. It tends to lean into those more abusive patterns.

How to regulate when dealing with children or young boys?

As the parent, there is a larger role of power and influence over a teen child, especially since your brain is more developed. We want to lean into you being more regulated if you’re leaning into any discipline, any correction, or if you want to teach emotional regulation, I’m a big person on modeling that behavior.

Also, unconditional or inherent love or acceptance of your child, no matter if they’re regulated or dysregulated, modeling that sense of behavior. That bond shows up as, again, what you’ve already done with your teenage sons, that bond is already there.

But if you’re noticing specific behaviors that you want to change or you want to model differently, or if you’re experiencing dysregulation within yourself, slowing that down and figuring out where that’s coming from.

Is that coming from a specific belief you have over yourself?

Are that specific behavioral problems that you’re looking at in your sons that you want to change?

How do you deal with someone who projects?

Someone who tends to project has a hard time seeing internally and building that sense of insight. When you see that projection coming through, it might be time to pause and stop. Because I don’t think in that moment you’re able to really get to that hurt, and that sense of shame.

When there’s projection, it means it’s hard to look at self. So they’re having a hard time looking within themselves to see what needs to be modified or changed or whatever need is not being met for use. I think they’re trying to think of them specifically.

Guilt and shame are the really big ones that we see as primary emotions. And when those triggers, we have all the protective parts that come through.

If you have specific questions for me that were unanswered today, please feel free to email me. For more information call (832) 559-2622 or text (832) 699-5001. You can schedule a free 15-minute consultation with any of our therapists.

Additional Resources:

- How Online Infidelity Affects Relationships

- Webinar: Couples Communication: Effective Strategies for Connection

Grounding & Self Soothing

Get instant access to your free ebook.